What is Holistic Wellbeing (Waiora)

Editorial by Rowan Aish

Holistic wellbeing (waiora or hauora), is a buzz word in the health sector, social services, and in the media, but what does it really mean?

What it means to ‘be well’ is different for everyone, and has changed over time. 100 years ago in the Western world, wellbeing was defined as simply the absence of disease, and it wasn’t until the World Health Organisation updated their definition in 1948, that we began to think of wellbeing as more than just physical health. Today, wellbeing is widely understood as encompassing physical, mental, spiritual, social, and environmental dimensions. Each of these are connected, and form part of the bigger wellness picture, which is why we refer to wellbeing as holistic.

“Wellbeing is a way of life oriented toward optimal health… in which body, mind, and spirit are integrated by the individual to live more fully within the human and natural community”

(Myers et al. 2000).

Māori definitions of waiora are unique, and draw on mātauranga Māori (traditional Māori knowledge). They may, for example, include the role of tīpuna (ancestors), atua (gods), and mauri (life force) (Pohatu & Pohatu, 2011). Māori definitions tend to place a greater focus on the collective waiora of the whānau, hapu, and iwi, and offer rich insights into the significance of wairua (spirituality) to overall health.

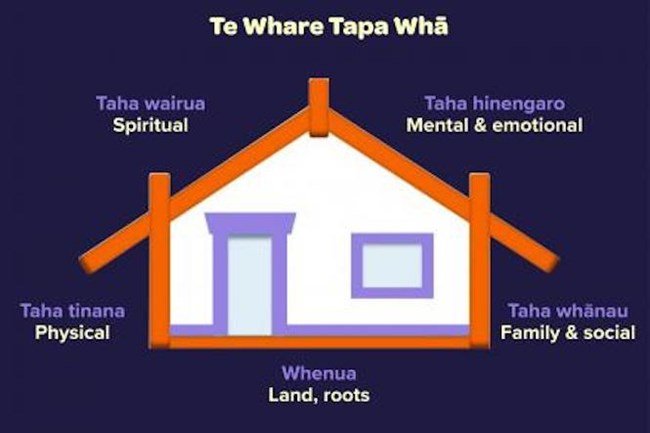

Te Whare Tapa Whā

Note: From Mental Health Foundation website.

Mason Durie’s Te Whare Tapa Whā model is an example of a Māori conception of wellbeing, and one that is widely applied within the New Zealand health context (Rochford, 2004). As the image shows, Te Whare Tapa Whā uses the four posts of the wharenui (traditional meeting house) to represent the four taha(sides) of wellbeing. If one of the taha is weakened, the strength of the whole whare (house) is compromised, demonstrating the interconnected nature of each aspect of waiora (Rochford, 2004). The wharenui is also a powerful symbol of Māori identity and collective belonging (McNeill, 2009), demonstrating the commitment to Māori values that underpin the Te Whare Tapa Whā model. A recent addition to the model as depicted here is the whenua (land/roots), which represents the importance of place and belonging to Māori conceptions of wellness.

Physical Wellbeing/Taha Tinana

As our population ages, and as more people with physical disabilities seek happy, meaningful, and fulfilling lives, the way that we think about physical wellbeing has evolved. It is now accepted that disease and disability do not necessarily exclude a person from attaining physical wellbeing. Rather, the emphasis is on the ability to perform basic functions, feel secure, and participate in meaningful work (Myers et al., 2000).

Exercise, a healthy diet, and adequate sleep are all things we can do to strengthen Taha Tinana.

Psychological Wellbeing/Taha Hinengaro

Psychological wellbeing is less about feeling ‘happy’, and more about being resilient in the face of adversity. Researchers also stress the importance of feeling loved, valued, optimistic, and confident in developing one’s potential (Hupper, 2009), as important markers of psychological health.

Māori often connect taha hinengaro with tūrangawaewae (a place to stand/belong), whanaungatanga (relationship), and cultural identity, each of which is central to the experience of positive psychological wellness for many Māori.

Connecting with a friend, engaging in meaningful and challenging work, and spending time in places we feel connected to, are some of the things we can do to strengthen Taha Hinengaro.

Relational Wellbeing/Taha Whānau

Holt-Lunstad (2017) suggests that close relationships and belonging to a group are innate biological needs, adaptive for human survival. This has been demonstrated in longitudinal research, such as the Harvard Study of Adult Development, that links social connectedness with reduced rates of illness and death. At the family level, for example, healthy attachment in childhood is linked with emotional health and resilience, as well as with better life outcomes (Bowlby, 1969). This is also true of one’s wider social connections, which are highly predictive of health behavior over the course of one’s life (Holt-Lunstad, 2017).

For Māori, Taha Whānau represents the collective wellness of the individual, whānau, hapu and iwi, and is a key concern for health professionals seeking to improve waiora for Māori (He Ara Oranga, 2018). Finding ways to strengthen Taha Whānau is an important part of the governments strategy for reducing intergenerational trauma and harm in Aotearoa.

Environmental health/Taiao

Another key dimension of health is taiao, or the physical environment we inhabit. Like the social environment, the whenua (land), air, water, flora and fauna, buildings, and other spaces we inhabit contribute greatly to our experience of and potential for waiora. The Ministry of Social Development (2003), for example, define a healthy environment as one which is “clean, healthy, and beautiful, [where] all people are able to access natural areas and public spaces” (p. 1).

For Māori, environmental wellbeing is reflected in the concept of tūrangawaewae, which represents home, belonging, and connection to a place (Royal, 2007).

Acting as stewards of our natural environment, whether directly through land restoration and protection, or through responsible waste management and consumption choices, is one way that we can strengthen our environmental health.

Spirituality/Taha wairua

No modern discussion of holistic wellbeing would be complete without mentioning spirituality. Wairua means many different things to many different people, however, one simple way of understanding this aspect of health is as the ‘uniting force’ that surrounds all other dimensions of wellbeing (Roscoe, 2009).

In te ao Māori, wairua is described as being “related to everything that was, is and will be Māori” (Valentine, 2016, p. 156), emphasizing the essentiality of wairua to Māori conceptions of wellbeing.

One way to strengthen wairua, is by connecting with something bigger than ourselves, whether it be based on religious beliefs, shared goals/values, nature, or something else.

Our commitment to wellbeing

At Kindred Family Services, supporting the holistic wellbeing of the individuals, families, and communities of North-West Rodney is an important part of our vision, and one that guides much of the work we do.

If you would like to support our work, please consider becoming one of our 100 founding Kindred Spirits by committing to a regular monthly donation.

References:

Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Volume 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Durie, M. (1994). Whaiora-Māori health development. Auckland, NZ: Oxford University Press.

He Ara Oranga (2018). Government inquiry into mental health and addiction [Government Report]. https://mentalhealth.inquiry.govt.nz/

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2017). Why Social Relationships Are Important for Physical Health: A Systems Approach to Understanding and Modifying Risk and Protection. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 437-458. https://www-annualreviews-org.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902

Hupper, F. A. (2009). Psychological wellbeing: Evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Applied Psychology: Health and Wellbeing, 1(2), 137-164. https://doi-org.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01008.x

McNeill, H. (2009). Māori models of mental wellness. Te Kaharoa, 2(1), 96-115. http://hdl.handle.net/10292/3325

Ministry of Social Development (2003). The Social Report 2003: Physical Environment [Government Report]. https://www.socialreport.msd.govt.nz/2003/physical-environment/physical-environment.shtml

Myers et al. (2000). The wheel of wellness counseling for wellness: A holistic model for treatment planning. Practice and Theory, 78, 251-266. https://doi-org.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb01906.x

Pohatu, T. W., & Pohatu, H. (2011). Mauri: Rethinking human wellbeing. Mai Review, 3, 1-12.

Rochford, T. (2004). Whare tapa wha: A Māori model of a unified theory of health. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 25(1), 41-57. https://doi-org.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/10.1023/B:JOPP.0000039938.39574.9e

Royal, T. A. C. (2007). Papatuanuku – The Land. https://teara.govt.nz/en/papatuanuku-the-land/page-5

Roscoe, L., J. (2009). Wellness: A review of theory and measurement for counsellors. Journal of Counseling and Development, 87, 216-226. https://doi-org.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00570.x

Valentine, H. (2016). Wairuatanga. In W. Waitoki & M. Levy (Eds.), Te Many Kai I Te Mātauranga: Indigenous Psychology in Aotearoa/New Zealand (pp. 43-70). The New Zealand Psychological Society.